Thanks to Mads and Wei for giving feedback on this.

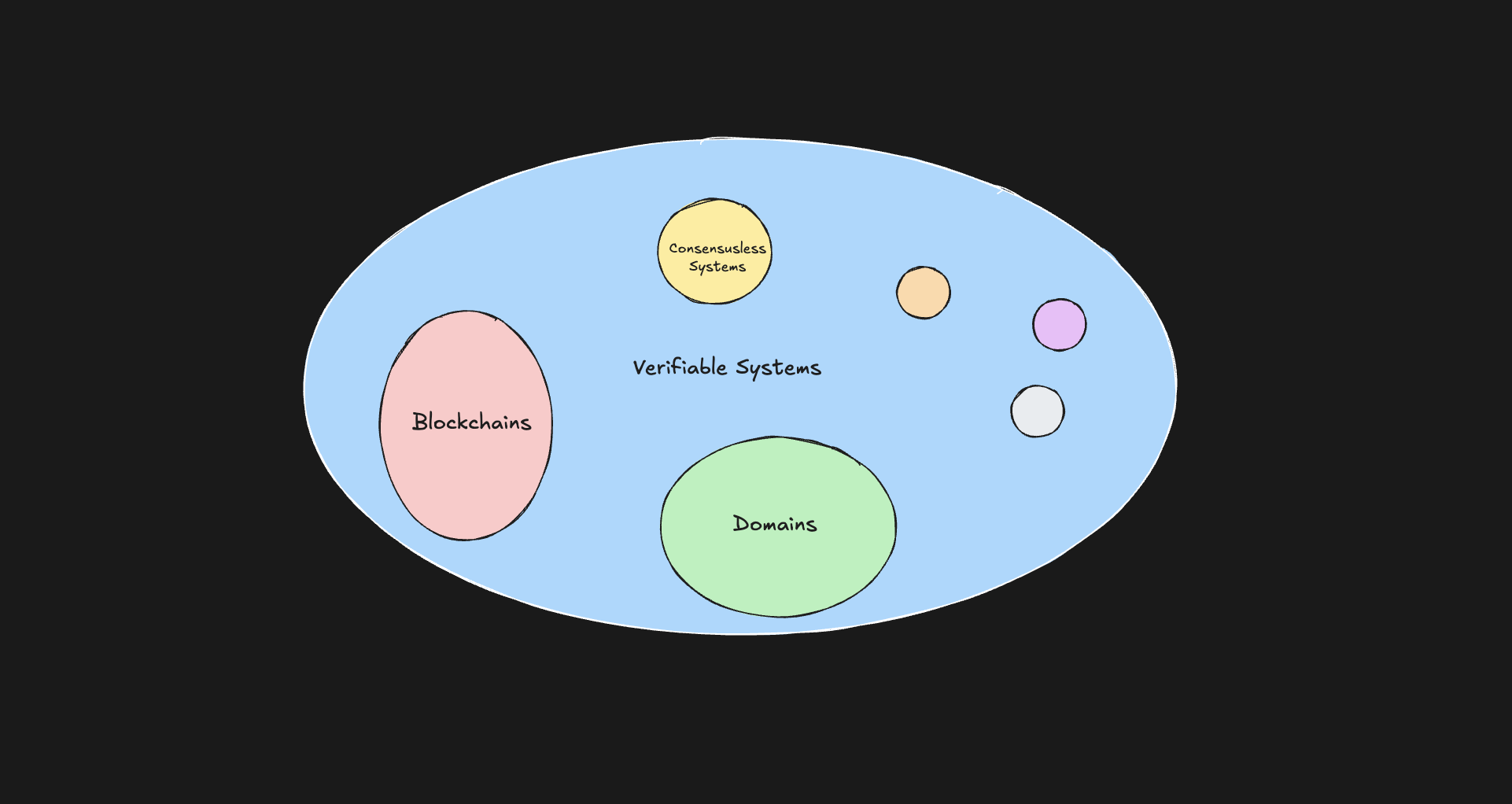

Blockchains are one kind of verifiable system—but we’ve treated them like the only kind. The implicit assumption that “chainness” is needed for the use cases we want is why the space has seen so little app-level innovation in the past 5 years.

Verifiable systems give us shared state, independently checkable updates, and self‑custody/exit. Because of this, they are great asset ledgers, enable trust‑minimized apps, and allow more automation. That’s really all.

Every blockchain is a verifiable system, but not every verifiable system has to be a blockchain. We have made this assumption, and it has cost us.

Over the last five years, we’ve made huge strides in scalability, languages, and tooling—yet the app surface looks mostly the same. That’s not a creativity deficit. It’s because blockchains have fundamental limits that optimization won’t erase.

As long as we try to solve everything inside the blockchain box, we’ll keep getting the same families of apps.

Example: Consensusless Verifiable Systems

Around 2018-2019, researchers proposed payment networks like Astro and FastPay that kept verifiability without global consensus. Both used strictly weaker primitives than consensus, which do not rely on ordering. More recently announced, Pod is another protocol of this flavor.

These types of systems maintain partially (instead of totally) ordered ledgers. You give up arbitrary computation, but you gain:

- Leaderless robustness (no single leader to stall the system);

- Throughput without a sequential block bottleneck;

- Lower latency (transactions confirm via a sort of verifiable mempool rather than waiting for block propagation).

These aren’t incremental tweaks to blockchains; they’re a different branch of verifiable systems. You cannot achieve these properties within the paradigm of blockchain.

The Fundamental Limits of Blockchains

- Determinism: The runtime is deterministic, so no syscalls, no OS time, no true randomness.

- No external I/O: As a result, contracts can’t read local files/DBs or fetch APIs directly. Oracles help somewhat, but they’re brittle, slow, and heavy compared to native reads.

- Large programs are infeasible: Gas for compute and storage plus a ballooning attack surface make rich onchain logic impractical.

There are more architecture‑level constraints: forced synchronicity within each transaction; awkward, risky upgrades; and deep reliance on chain‑specific middleware. These aren’t fixable; they’re design choices.

So why pour all our energy into squeezing more scalability out of blockchains while spending so little on more capable verifiable systems?

Fundamental to Blockchains, not in General

These constraints are blockchain‑specific, not inherent to verifiable systems. There are “blockchain‑y” state machines that preserve shared state, verifiability, and self‑custody without the programmability limits of chains. One such class we’re developing is domains, a new subcategory of verifiable systems. (Details in the linked piece.)

Since Ethereum, the crypto space moved straight into 1-N mode, when there are still huge 0-1s yet to be solved. We have to design verifiable systems from first principles, not just better blockchains. In the same way that databases are bigger than SQL, verifiable systems are bigger than blockchains. And most have yet to be discovered.