Programming GPUs used to be really hard. In order to write in the assembly-like shader languages exposed by the chips, the developer would have to think in the graphics-based terms of the hardware (triangles, pixels, framebuffers), instead of the standard high-level programming concepts they used in their day-to-day (“launch N threads over this array”). Effectively, they had to maintain two completely independent systems, the normal host code and a graphics‑shaped GPU codebase, each with its own tooling and concepts.

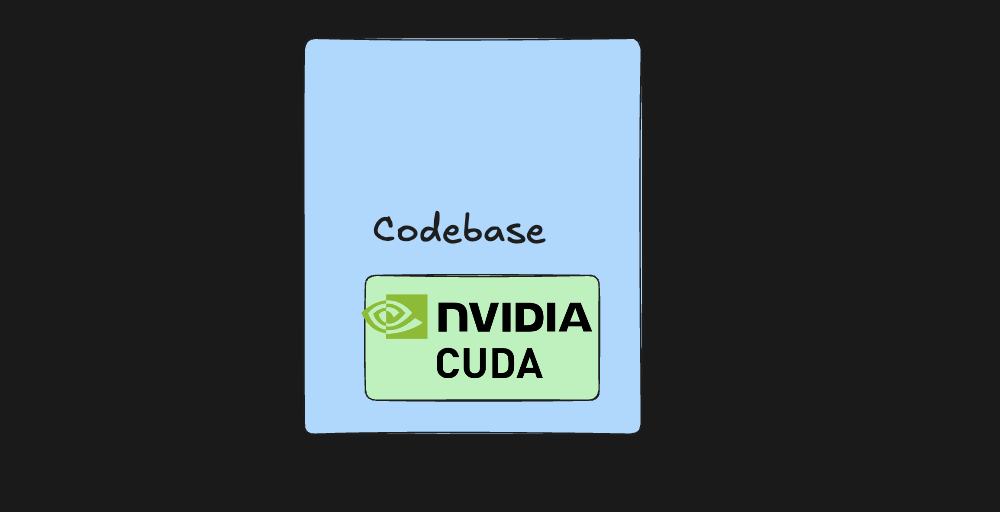

This remained true until CUDA hit the market in 2007. CUDA made interfacing with the hardware much more intuitive by letting programmers write kernels in C/C++ and giving them access to a toolchain that made sense to them. The upgrade was similar to the jump from assembly to high-level programming languages about three decades earlier. You still benefited from understanding GPU specifics, but the work fit into the existing stack and the surrounding libraries (cuBLAS, cuFFT, later cuDNN/NCCL) made high performance accessible.

Blockchains are the GPU

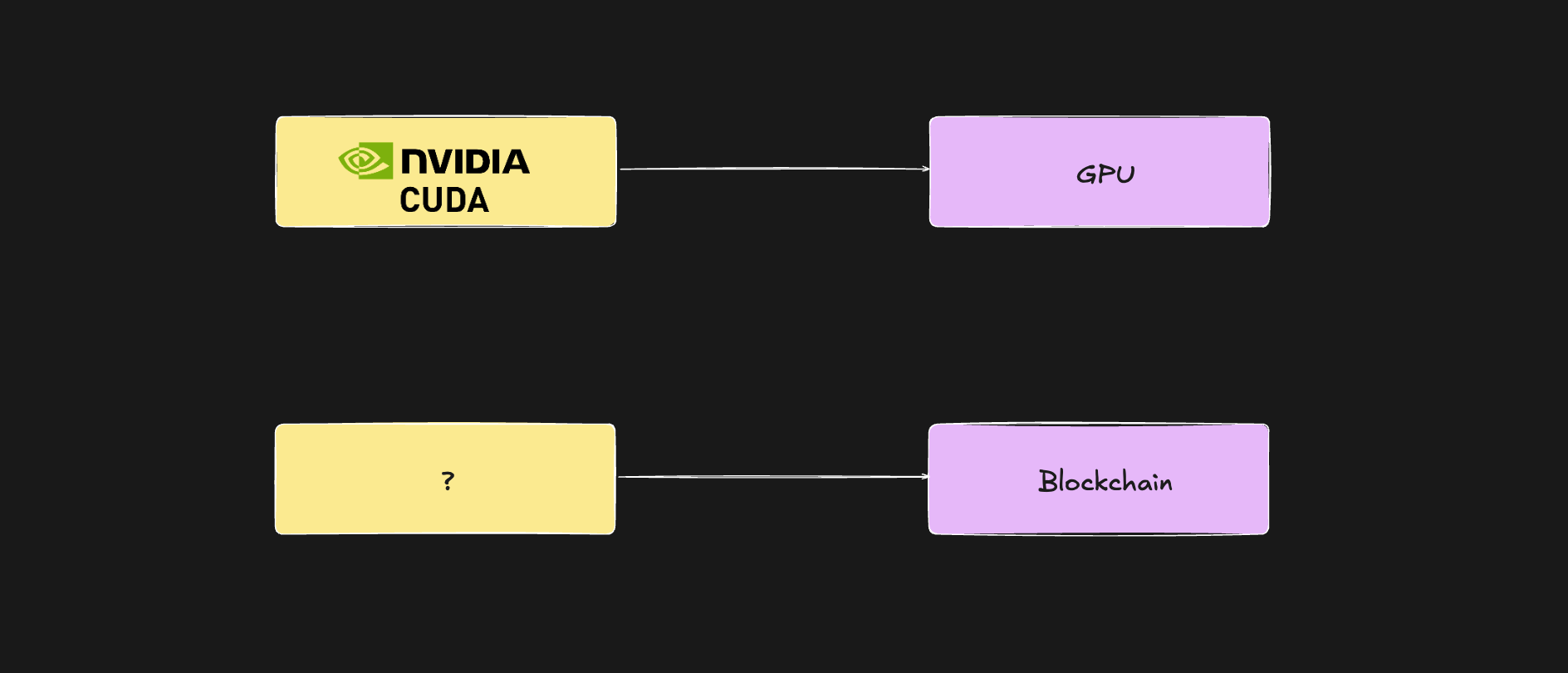

People use GPUs because they deliver massive parallel throughput on linear algebra-like workloads. Because they had no choice, they were therefore willing to suffer through the experience of programming these things directly.

Similarly, people use blockchains because of certain properties only they provide. You deploy your application to a blockchain because you care about access to assets or interoperability of something like that. In order to do so, you have to build it from scratch within the “computer” of the blockchain itself. Similar to the pre-CUDA GPU era, this means that you have to rewrite all the parts you want to benefit from the blockchain inside the blockchain itself.

The problem with programming blockchains is not the language, as it was for GPUs. It’s not even necessarily the extended toolkit, although this is severely lacking relative to traditional software. The sacrifice required in the case of blockchains is in capability: By moving your logic to a blockchain, you are severely restricting what it can do. Almost certainly it will not be able to work exactly the way you’d want it to, as you’re suddenly cut off from APIs, the operating system, and the code is extremely size-constrained. Even if you were to be able to split your codebase into offchain and onchain, you would now have two completely independent systems running asynchronously, only able to interact with each other through slow, unreliable blockchain middleware.

Blockchain Nvidia

Nvidia won not because of the chips, but because of the software platform enabled by CUDA. With CUDA, most teams don’t learn the graphics pipeline or hand‑write kernels everywhere; they call familiar APIs and, where needed, drop in small CUDA kernels. The stack does the heavy lifting.

The blockchain analog needs the same move. If the chain is the GPU, the missing piece is a CUDA‑like layer that lets engineers reach shared, verifiable state from normal services, without rebuilding their apps as monolithic smart contracts.

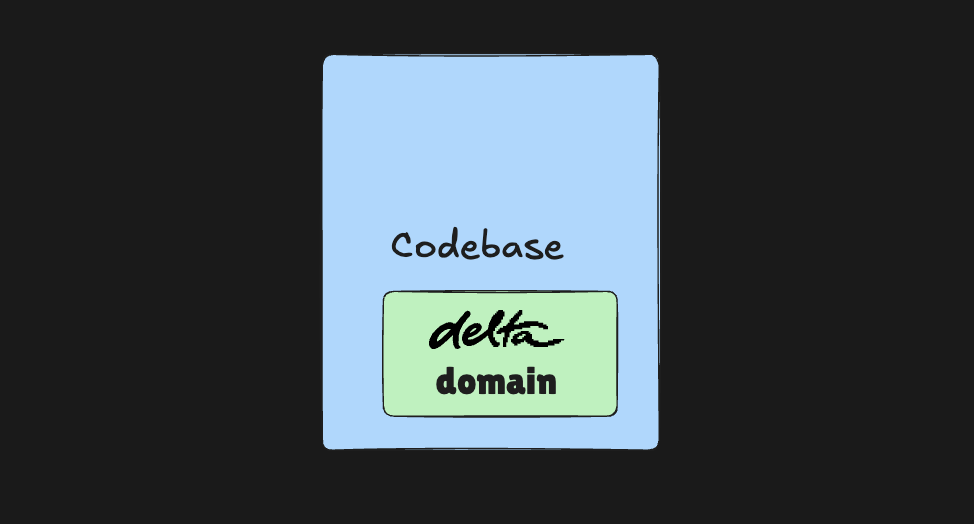

That’s what we’re building with delta’s domain SDK. delta is a permissionless, verifiable ledger; the domain SDK is the runtime and libraries you import into your codebase to selectively add verifiability and interact with the delta shared state (similarly to smart contracts).

In practice, you add a small set of domain-specific calls/annotations wherever you want onchain guarantees—sharing state on delta or stamping results with verifiability—while the rest of your architecture stays the same. The SDK absorbs the chain’s quirks; your team keeps its tools and velocity.

CUDA:GPU::domain SDK::verifiable system